Building a Fiction AST and Training a NER Model with GLiNER

My wife recently completed her MFA in creative writing. For the past couple of years, I’ve been her sounding board. Her world is character arcs, unreliable narrators, and the rhythm of sentences. Mine is build systems, developer tools, and making computers do tedious things fast.

She’d describe a problem and I’d think: that’s a linter. My brain kept mapping her writing problems onto the developer tooling I am intimately familiar with. What she was describing, without knowing it, was a prose LSP — a Language Server Protocol for fiction.

I’ve spent years in Developer Relations building and advocating for exactly this kind of tooling. The realization that fiction writers have the same fundamental problems as software engineers (consistency, tracking references, catching errors across large files) was the spark.

So I did what any reasonable engineer married to a writer would do in 2026 I started vibecoding a custom Abstract Syntax Tree (AST), eventually supplementing that with a named entity recognition (NER) model.

Due to my employment at Google, the dataset, model weights, and source code for this project are not publicly available. I want to share the architecture, pipeline, and what I learned building it.

The Fiction AST

I started by parsing stories into an AST of chapters, scenes, paragraphs, sentences, and words. Each word was tagged via a part-of-speech (POS) tagger, and each sentence was classified by type, e.g., dialogue, narration, etc. I then pulled metrics up the AST to surface things like tempo, pacing, and sentence length.

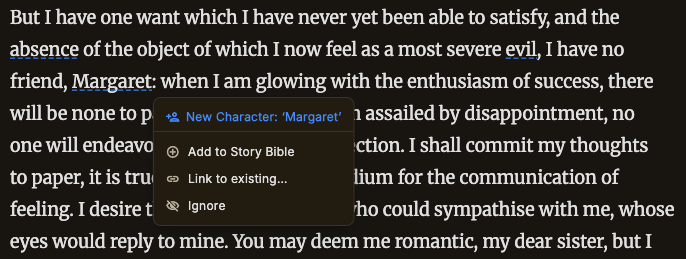

I quickly realized how valuable identifying characters would be for my prose LSP. Many novels have complex worlds, with diverse characters that need to be tracked. I looked back to the POS tagger, but quickly realized that it was insufficient for the task. A quick hack was to check a dictionary against all capitalized words, and if it wasn’t in the dictionary, assume it might be a named entity. This just generated massive amounts of noise, so I turned to ML after some conversations with AI.

Fiction NER Is Hard

In my research, I found that off-the-shelf NER models are trained on news articles and encyclopedias. They’re great at extracting “Barack Obama” and “Washington, D.C.” from a news clipping, but some arbitrary name in fiction wouldn’t fare so well.

Characters have nicknames. Locations are imaginary. The model needed to know much more than what it had learned from newspapers and other sources.

The constraint I set for myself was that the model had to run entirely inside a Rust application. No Python, no GPU, no cloud API at inference time. If this was going to be a real prose LSP component, it needed to be fast, private, and local.

Why GLiNER?

I’m not an ML researcher. I’m a DevRel engineer who vibecodes various apps and try to help other developers do the same.

While not an ML researcher, I fortunately took a couple of graduate courses in statistics and spent a few years working on the analysis of satellite imagery using machine learning.

GLiNER (Generalist and Lightweight Named Entity Recognition) turned out to be the right tool for the job. It’s a span-based NER architecture that takes plain-text label descriptions as input alongside the text. You pass labels like ["person", "location", "time"] at inference time, and it finds matching spans. No fixed label set is baked into the model.

This matters because:

- Zero-shot capability — GLiNER generalizes to labels it hasn’t explicitly seen during training, making it easy to experiment with new entity types.

- Small footprint via Quantization — The base FP32 model is large to be bundled locally, (~634 MB), but by applying quantization during the ONNX export, I reduced the payload to ~188 MB. Small enough to bundle into a Mac/Windows desktop app.

- No tokenization alignment headaches — GLiNER operates on word-level spans, not subword tokens, so character offsets map cleanly to the original text. This is critical for an LSP-style tool where you need to underline exact words in a text editor.

The tradeoff: pre-trained GLiNER models struggle with fiction. Fine-tuning is essential.

The Pipeline

The full pipeline looks like this:

Raw Stories → Chunks → LLM Labels → Parsed Spans → Fine-tuned Model → ONNXEach stage produces a JSONL artifact that feeds the next. The whole thing is held together with Rust CLI tools, Python scripts, and some vibecoding.

Data Sourcing

I assembled a corpus of ~6,500 fiction texts from two sources:

- Project Gutenberg — Public domain novels and short stories. Excellent for literary fiction but over-represents 19th-century prose.

- BookCorpus — A large dataset of unpublished books by independent authors. Contemporary fiction with modern dialogue and varied genres to balance the older texts.

I wrote a cleaning pipeline that strips everything except pure story prose — author notes, word counts, and document annotations all get removed.

Chunking

Full novels are too long for LLM context windows and too expensive to label in one shot. I built a Rust-based chunker that uses the AST parser I had already written to split stories into training-sized chunks.

The chunker:

- Parses each story into an Abstract Syntax Tree of paragraphs and sentences

- Accumulates sentences until hitting a target word count (~200 words)

- Respects paragraph boundaries to avoid splitting mid-thought

- Removes scene break markers, inline TOC blocks, and chapter headings

This produced hundreds of thousands of clean prose chunks, each 150–300 words, ready for labeling.

LLM Labeling (Distillation)

This is the core interesting part of the whole project that was new to me: use a large language model to generate training labels for a small, fast model. When I worked at USGS, I built a pipeline and web applciation to quickly, but manually generate labels for satellite iamgery and it still took weeks to label enough data to train a model.

I used Gemini 3 Flash to wrap entities in XML tags:

Input: Colonel Doyle arrived at the Savoy on Tuesday night.

Output: Colonel <person>Doyle</person> arrived at the <location>Savoy</location>

on <time>Tuesday</time> night.The labeling script sends each chunk to the LLM with a carefully tuned system prompt.

The system prompt includes:

- Label definitions from a YAML config defining ~30 entity types organized into categories (core narrative, character & identity, physical world, sensory, abstract, speculative fiction)

- Per-label precision guidance — e.g., for

person: “Named characters only. Do NOT tag pronouns, generic descriptors, bare titles without a name, or deity names.” - Explicit negative examples — “the hall” is not a location, “Colonel” alone is not a person, “night” is not a time reference

- Formatting rules — preserve exact original text, exclude leading articles from spans, no nested tags

The labeling runs with async concurrency (20 parallel requests), retry logic with exponential backoff, and resume support. A full pass over 10,000 chunks takes a few hours and costs a few dollars in API credits.

Why distillation instead of hand-labeling? Who has time to label 10,000 text chunks for fun? An LLM with detailed prompting gives you 90%+ quality at 1000x the speed. The fine-tuned GLiNER model then compresses this knowledge into something that runs in milliseconds on a CPU. The local AI Gemini interface in my IDE was also great at doing spot checks, generating reports, and then iterating on the prompt.

Parsing Labels to Spans

The LLM outputs XML-tagged text, but GLiNER needs character-offset spans. A parsing script handles the translation:

- Strips XML tags and reconstructs the plain text

- Records

[start_char, end_char, label]for each entity - Validates that the reconstructed text exactly matches the original (catching LLM hallucinations)

- Normalizes label synonyms (e.g., mapping invented labels like

"place"to"location") - Filters down to a configurable label preset

I trained with a focused preset of just three labels: person, location, and time. Starting narrow lets the model learn the hardest distinctions well before expanding and I really didn’t care about many of the other labels.

The final training dataset was 9,430 samples with validated character-offset spans.

Fine-Tuning

The training script fine-tunes gliner-community/gliner_small-v2.5 using the GLiNER library’s built-in trainer:

PYTORCH_MPS_HIGH_WATERMARK_RATIO=0.0 uv run train_gliner.py

--model small

--input data/gliner_spans_focused.jsonl

--epochs 3Key hyperparameters:

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Base model | gliner_small-v2.5 |

| Learning rate | 5e-6 |

| Batch size | 2 |

| Gradient accumulation | 4 (effective batch = 8) |

| Warmup ratio | 0.1 |

| Weight decay | 0.01 |

| Epochs | 3 |

| Dev split | 10% |

Training takes ~3 hours on my 2024 MacBook Pro. The PYTORCH_MPS_HIGH_WATERMARK_RATIO=0.0 environment variable prevents MPS memory allocation failures — it tells PyTorch to use a more conservative memory strategy at the cost of some speed.

Results

Evaluation on the held-out dev set:

| Label | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| person | 0.925 | 0.946 | 0.935 |

| location | 0.851 | 0.928 | 0.888 |

| time | 0.641 | 0.859 | 0.734 |

| Overall | 0.868 | 0.932 | 0.899 |

person extraction is strong — the model learned to distinguish proper character names from pronouns, titles, and generic descriptors. location is solid but occasionally over-triggers on generic place words. time is the weakest, which makes sense; temporal expressions in fiction are wildly varied, and the boundary between a taggable time reference and ordinary narration is genuinely fuzzy.

ONNX Export

To run the model inside a Rust application without Python, I exported it to ONNX:

uv run export_gliner_onnx.pyThis produces:

model_fp32.onnx— Full-precision model (fallback, ~634 MB)model_int8.onnx— Dynamically quantized 8-bit integer model (~188 MB)tokenizer.json— DeBERTa tokenizer for the Rust runtimegliner_config.json— Model configuration

The conversion uses onnxconverter-common with keep_io_types=True to maintain FP32 inputs/outputs for compatibility, which is then dynamically quantized to INT8 to optimize for CPU inference.

Rust Inference

Because the community gliner-rs crate had FFI version conflicts with modern ONNX runtimes, I vibecoded the full GLiNER pipeline natively in Rust:

- Word splitting — regex-based tokenization matching GLiNER’s expected input format

- Prompt construction — builds the

[<<ENT>>, label1, <<ENT>>, label2, ..., <<SEP>>, word1, word2, ...]sequence - Subword encoding — tokenizes each word individually with the DeBERTa tokenizer, building attention masks and word-position mappings

- ONNX inference — feeds the six input tensors to the model

- Sigmoid decoding — applies sigmoid to logits and extracts spans above a confidence threshold

- Greedy deduplication — removes overlapping spans, keeping the highest-scoring ones

The Byte-Offset Trap: The hardest part of this pipeline wasn’t the ML math; it was wiring the ML predictions back into the deterministic AST. Because GLiNER inherently knows the exact byte boundaries of the spans it extracts, I had to rewrite the AST ingestion to resolve entities by intersecting the exact byte ranges of the text tokens with the byte ranges of the ONNX output tensor.

The Scale Optimization: Running an 85-million parameter model on every single sentence of a 100,000-word novel would destroy a laptop. I added a pre-flight lexical gate that skips inference entirely on sentences unlikely to contain named entities (e.g., no uppercase letters after position 0, no digits). In fiction, ~40% of sentences are pure action beats or short dialogue. Bypassing the model for those lines drops inference time, keeping the AST parse instantaneous.

What I Learned

Vibecoding works for ML pipelines. I didn’t have a rigorous research plan. I had conversations about fiction and a weekend urge to build something. The iterative loop of “prompt the LLM, look at the output, fix the prompt” was highly effective.

Start with fewer labels. I initially tried the full 30-label set and got poor results across the board. Focusing on three high-value labels produced a genuinely useful model. You can always train a second model later.

Developer tooling patterns transfer to creative writing. An LSP for prose isn’t a metaphor, it’s a literal architecture. Tokenizers, AST parsers, diagnostic spans, background analysis on keystroke. The hard part was never the engineering. It was learning enough about fiction (and English) to know what to analyze.

© 2026 by Justin Poehnelt is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0